Everyday Life

Unfree Labor

Early colonists who arrived in America eked out a living primarily through subsistence farming: growing food to feed your family. Through time, subsistence farms and small cash crop fields became plantations—some stretching over thousands of acres. In the Chesapeake, most of these plantations grew and harvested the extremely profitable crop of tobacco.

Labor demands expanded as early Americans began to successfully farm crops and accrue more arable land. Throughout much of the 17th century this need for more labor was satisfied by the recruitment of indentured servants. This workforce was primarily composed of European immigrants, who could not otherwise pay the steep cost of passage to America. Plantation owners also provided room and board in exchange for four to seven years’ worth of labor. After this period of indentured servitude the individual would find themselves a freeman in the colonies.

The labor needed to profit from a tobacco plantation was significant, and planters began to invest in enslaved laborers who would be bound for life. Between 1690 and 1770, one hundred thousand people of color were imported into North America, almost all from Africa. These enslaved Africans were traded and sold throughout the American colonies to work in agricultural and domestic tasks.

In Maryland, Jesuit priests initially acquired plantations to fund their missionary and educational work. Jesuit brothers usually oversaw plantation management. The origins of slaveholding within the Society of Jesus is poorly understood. For most of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, indentured and enslaved laborers principally cultivated tobacco and corn. Jesuits contracted overseers to manage enslaved laborers.

Read more about early American slavery: Alan Kulikoff, Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680-1800 (1988).

Tobacco

Tobacco was a staple of Maryland’s colonial economy, and enslaved Africans were first acquired by the Jesuits in order to cultivate tobacco. Growing tobacco was no small task, from seeding to harvesting and curing the whole process took close to a year. The tobacco seed beds were begun in January or February, crops were seeded in March, and thinned in April. Experienced field hands prepared the fields and transplanted seedlings in May.

Maintenance of the fields from weeds and worms was necessary to ensure crop survival, as was careful pruning or “topping” of the plants. Children were expected to pick and crush worms, which could destroy the plants. Harvest occurred in late August or early September, followed by a month-long curing period, then “sweating,” sorting, and packaging into large barrels called hogsheads for shipment to Europe.

Read more about cultivating tobacco.

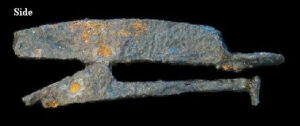

Smoker’s companions are multi-purpose tools used by smokers to tamp, light, and clean their pipes. This one is from the Buck Site in Kent County (learn more). Images courtesy of the Maryland Historical Trust/Maryland Archaeological Conservation Laboratory.

Daily Life

Daily life in early America started around 5 o’clock, as the sun rose, and did not end until after the sunset. Working the fields was difficult and exhausting; landowners often exploited indentured servants or enslaved Africans in order to more profitably plant and harvest crops. In addition to working 12-14 hours each day in tobacco fields, enslaved laborers completed domestic tasks for their own households, cooking with provisioned rations and produce from their own gardens. Enslaved Africans also worked in Jesuit households as cooks, housekeepers, personal servants (“priests’ boys”), and grooms.

Families were usually large; a typical family consisted of a mother and father, and four to six surviving children—although enslaved families could be separated by sale. Work was often conducted according to the seasons and the need to sow or reap crops. Men worked in the fields, and built or mended farm infrastructure such as structures, fences, and ditches. Hunting, fishing, and oystering were also necessary skills, as most crops were grown to be sold rather than for subsistence. Women spent the winter and spring months spinning thread and sewing, and the summer and fall months gathering and storing fruits and vegetables. Women worked diligently to upkeep the household, did the majority of the cooking, and educated young children. Children growing up on a plantation learned largely about how to perform practical tasks. Sometimes, boys were taught reading and writing.

Daily life in early America started around 5 o’clock, as the sun rose, and did not end until after the sunset.

Read more about daily life on a large plantation.

Housing

Early plantation houses were relatively simple “earthfast” structures, generally with one or two rooms totaling 16 by 20 feet. The floor was often dirt, but sometimes made of wood. A hearth was a focal point within the house, as it was used for cooking and warming the interior space. Upstairs lofts were generally built for storage or extra sleeping space. By the early 1700s, wealthy plantation owners like the Jesuits were able to build larger houses, often of brick. Additional outbuildings were constructed for purposes such as housing enslaved and indentured laborers, drying and storing meat, processing dairy products, storing crops, or housing livestock.

On Jesuit plantations, enslaved Africans usually lived in “quarters” or “cabins” fitted with bunks and a kitchen space. These buildings were of inferior construction, often built of logs. The size of quarters varied, often consisting of a single main room measuring 12×12 or 12×16 feet to accommodate a family or group of unrelated persons. Archaeology is often the only way to identify the location of wooden buildings that no longer stand. While “postholes” mark the location of timber-framed buildings, log houses can be nearly impossible to identify. Subfloor pits and a light scatter of pottery and tobacco pipes are often all that remains of slave quarters.

Read more about earthfast housing.

Necessities

Historical documents provide some information about enslaved persons’ use of material objects in everyday life. At Bohemia, the enslaved community was provisioned with clothing in the summer and winter. For men living during the 1790s, this included two shirts and one pair of linen trousers during the summer, and breeches or trousers, a woolen jacket, yarn stockings, and shoes in the winter. Women were allotted two shifts and a petticoat for the summer, and one woolen shirt gown and petticoat, one pair of shoes, each winter, and a pair of yarn stockings every other year (read more here). Blankets were also distributed “as needed” during the winter.

At St. Thomas, enslaved women were responsible for spinning, knitting, and weaving the striped cloth used to make these clothes. An enslaved shoemaker was busy ensuring that 60 persons had shoes to wear (read more here). A “weaver’s house,” where enslaved women may have labored, is documented in the ca. 1820 map of St. Inigoes.

Members of enslaved communities were also resourceful, using earned cash to purchase their freedom and purchase additional things for themselves. At St. Inigoes, George purchased a coarse fabric called “Osnaburgs” in 1734, probably to make clothing. That same year, Betty used “Sprig Linnen” to line her clothing.

House furnishings were minimal, as was entertainment. Religious practices, music, communal meals, smoking tobacco through white clay pipes provided important avenues for social life—and often left material traces. Most of the artifacts excavated from sites like St. Inigoes, Newtown, and Bohemia—tobacco pipes, pans for cooking and dairying, animal bones and oyster shells, nails, and dark green glass from wine bottles—would have been used regularly by enslaved persons.

Jesuit Mission

Catholics arrived in Maryland among the first colonists in 1634, settling in the area that is now known as St. Mary’s City. Among the colonists was Rev. Andrew White, a Jesuit missionary who founded the mission that became St. Ignatius Church at Chapel Point. Following a century of religious tumult in England, Catholic colonists were eager to establish a religiously tolerant society in Maryland. Missionaries also sought to convert English Protestants, as well as Piscataways and other Native communities. The profits raised from tobacco cultivation allowed the Jesuits to expand their land holdings, run schools, and establish active missions.

Jesuit missionary life could at times be strenuous as it often involved traveling long distances to say mass and administer the other sacraments. Speaking of the missionary’s experience in eastern Pennsylvania, Father Theodor Weber wrote in 1750:

In contrast, priests in southern Maryland returned to opulent brick houses, feather beds, large libraries, wine cellars, and a household cared for by enslaved laborers.

Catholicism & Slavery

Enslaved Africans transported to early America brought with them a rich and diverse tradition of spiritual practices and beliefs. These traditions included the practices of Indigenous cultural groups in West Africa, as well as the long-term influences of Christianity and Islam. While certain customs, songs, ways of preparing food, and natural medicines were preserved, persons enslaved by the Jesuits also began to integrate Catholic practices into their expressions of community and spirituality.

Catholic practices were not altogether dissimilar from West African religious traditions, which included communal singing, praising, dancing, and spirit worship. It is difficult to track exactly how Catholicism influenced the lives of enslaved African peoples, as their tradition was mainly an oral one. While subfloor pits may have functioned as West African ancestral shrines within some slave quarters, Roman Catholic devotional objects are also found across African American sites in Maryland, such as Northampton Quarter. African American Catholicism took root early in Maryland. Enslaved Africans suffered and survived the impossible difficulties of enslavement and sale through their own faith and strength of will.

Reliquary in the form of a Cross

Virtual Curation Lab (VCU_3D_6824)

Crucifix Plaque

Virtual Curation Lab (VCU_3D_6823)